As half of the global human population, women have a significant impact on world history. Often overshadowed by a patriarchal view in most historical accounts, the inspirational achievements of women are no less significant. On this International Women’s Day 2020, Geek Girl Authority looks at the lives and endeavors of a few women that helped define human history.

Servilia

History probably best remembers Servilia Caepionis as the mother of Marcus Junius Brutus, but Servilia was a historical power player in her own right. Married to Decimus Junius Silanus, Servilia was a well-connected Roman aristocrat. In 64 BC, Servilia began an affair with Gaius Julius Caesar. Caesar would go on to enter the upper echelons of Roman society by 60 BC with the establishment of the First Triumvirate. This was an informal alliance between Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (or simply “Pompey”), and Marcus Licinius Crassus. Servilia was one of a number of women who leveraged their wealth and connections to gain political and economic power in the Roman Republic. Across multiple decades, Servilia acted as the most important back channel for Rome’s politicians.

It was Servilia that advised Caesar to take advantage of his provincial governorship to seek fortune and conquest (setting the stage for Caesar’s conquests in the Gallic Wars). In addition, she advised a young Brutus to side with Pompey after Caesar crossed the Rubicon (in spite of her personal feelings for Caesar). Though Servilia truly loved Caesar, her loyalty was first and foremost to her son Brutus and the future of her family. So much that when Brutus and the Roman Senate conspired about the assassination of Caesar, they did so at Servilia’s house.

Cleopatra

The historical Queen Cleopatra VII Philopator of Egypt was more than simply a great beauty. First and foremost, Cleopatra was an intellectual. Ambitious and driven, Cleopatra desired power above all things. When Gaius Julius Caesar arrived to Egypt, the Ptolemaic kingdom was embroiled in a civil war between Cleopatra and her brother (and husband, ew) King Ptolemy XIII. Caesar was placed under house arrest after refusing to ally with Ptolemy. Seeing a way to reinforce her losing side of the civil war, Cleopatra frees Caesar in exchange for his support. In 47 BC, the Roman legionnaires lay siege to Alexandria. During this siege, Cleopatra and Caesar became lovers. Though she is infamously portrayed as a seducer in history and popular culture, both Cleopatra and Caesar desired power and admired each other’s’ political skills. It was Cleopatra who put the idea of monarchy in Caesar’s head when he returned to Rome.

A year later, Cleopatra followed Caesar to Rome. Rome was a patriarchal society, but Cleopatra was not the type of woman to ever submit to a man. Cleopatra was a queen in her own right, for which the Roman Senate found her “arrogant.” After Caesar’s assassination, Cleopatra returned to Egypt and would years later come to be lover and spouse to Caesar’s protégé: Mark Antony. However, her dream of an independent (or at least quasi-independent) Egypt would die along with Cleopatra and Antony when they committed suicide in 30 BC. Regardless, Cleopatra defined Mediterranean politics in the last two decades of the Roman Republic. The fact that this queen so greatly influenced the fates of not one, but two, Mediterranean states speaks to the power and ambition of the Queen of the Nile.

Mara Branković

Mara Branković was the daughter of Serbian despot Đurađ Branković. In 1435, Princess Mara entered the Ottoman harem when she became the third wife of Sultan Murad II. Murad II separated a young Mehmed II (future “Mehmed the Conqueror”) from his mother and brought him to the Ottoman capital of Adrianople (modern-day Edirne). Thankfully, Mara comforted the young prince. Mara became stepmother to Mehmed II and took him under her wing. When Mehmed II took the throne as sultan, it was “Mother Mara” who was his first and most important ally. Despite an offer of marriage from Emperor Constantine XI of Constantinople himself, Mara decided not to retire to obscurity after her husband Murad II’s death. Instead, she became an important adviser in the Ottoman court.

Sultan Mehmed II had the utmost respect for Mara Branković and her support was crucial for his reign. In addition to being a Serbian princess, Mara had family relations in Western Europe. Not to mention, the royal family of Constantinople (which Mehmed II would soon conquer). A popular saying is that “behind every great man is an even greater woman.” Without Mara’s support for Mehmed II before and even during the siege of Constantinople, it’s possible that the greatest victory of the Ottoman Empire would never have succeeded.

Queen Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth I succeeded the English throne after the death of her sister Queen Mary I of England in 1558. She was the sole surviving child of King Henry VIII. Queen Elizabeth I and her reign were a synthesis of extremes. In some areas, Elizabeth was short-tempered and indecisive. In other areas, she was tolerant and a charismatic survivor. On religious issues, Elizabeth avoided systematic persecution of Catholics, even as Pope Pius V excommunicated her. In addition, he demanded that her cousin Queen Mary I of Scotland replace Elizabeth. England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 is praised as one of the greatest military victories in human history.

Art, literature, and drama flourished during her reign. The Elizabethan era is celebrated as the height of the English Renaissance. Though many of the issues tackled during Elizabeth’s reign would persist even after her death, the reign of Queen Elizabeth I was undoubtedly one of stability. Faced with stronger foreign powers like France and Spain, Elizabeth forged a sense of national identity that would persist for centuries to follow.

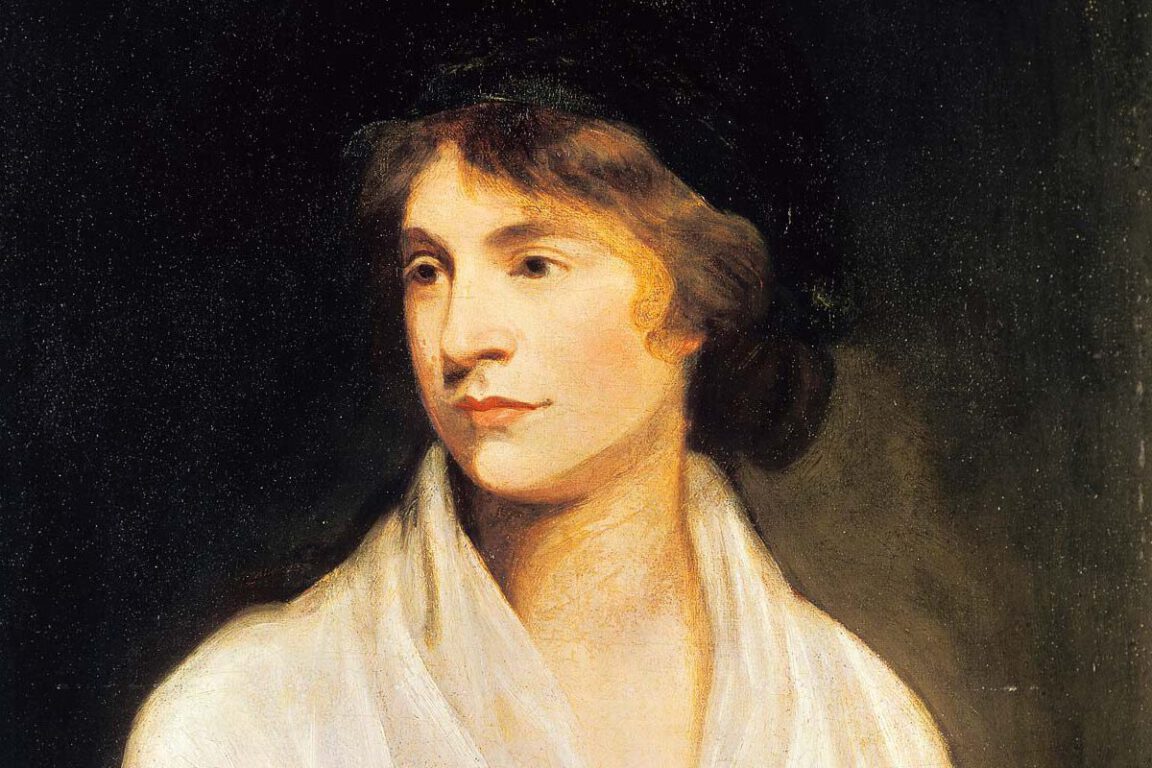

Mary Wollstonecraft

Often confused for her equally famous and talented daughter (Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the author of Frankenstein), Mary Wollstonecraft was an English writer and philosopher. She championed the education and liberation of women. Her book A Vindication of the Rights of Women was written against the backdrop of the French Revolution. Arguing for the equality of women and men, A Vindication of the Rights of Women cites that women are not inferior to men. On the contrary – they appear inferior due to lack of a formal education for most women.

A year after her death, Wollstonecraft’s newly-widowed husband William Godwin published Memoir of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1798 as a compassionate and sincere portrayal of his beloved wife. Unfortunately, the late 18th century readers of the memoir were scandalized by Wollstonecraft’s love affairs, illegitimate children, and suicide attempts. Opponents of Wollstonecraft were quick to capitalize on the memoir with vicious satires. In spite of the inadvertent damage to Wollstonecraft’s reputation, her writings were discreetly circulated throughout English society. They even influenced English women such as Jane Austen. With the rise of the feminist movement in the early 20th century, Wollstonecraft’s works were gradually rediscovered and reintroduced into mainstream society. Wollstonecraft’s writings are now celebrated as some of the founding texts of modern feminism.

Vera Atkins

A Jewish Romanian who emigrated to Britain as fascism was on the rise in 1930s Europe, Vera Rosenberg adopted “Atkins” (the Anglicization of her mother Hilda’s maiden name) as her new surname. Vera Atkins was a talented linguist, having studied modern languages at the prestigious Sorbonne of the University of Paris. When Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1939, Atkins was recruited for the British military mission to extract the Polish codebreakers who had broken Germany’s Enigma codes back in 1932. Atkins arranged for the Poles’ release from internment in then-neutral Romania and their travel to Western Europe.

In 1941, Atkins joined the newly-formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) of British military intelligence. Atkins was responsible for the training and deployment of 37 female SOE agents into occupied France. Though unpopular with many of her colleagues, Atkins was trusted by her section head for her integrity, exceptional memory, and good organizational skills. After the end of World War II, Atkins set out to find the 118 SOE agents who were still missing-in-action. Atkins was able to trace 117 out of the 118 of her missing “girls.” For her wartime service, Atkins was awarded by France with the Croix de Guerre in 1948 and made a Commandant of the Legion of Honor in 1987.

RELATED: Read all of our International Women’s Day posts here!

- STAR WARS: Most Powerful Sith Lords - May 4, 2024

- GGA’s Favorite Foods From Our Favorite Video Games - February 5, 2024

- What You Should Know Before EXANDRIA UNLIMITED: CALAMITY - May 25, 2022